(RNS) — With Friday’s U.S. Supreme Court ruling overturning Roe v. Wade, the religious right can take a victory lap.

The movement’s ability to overcome theological differences and build a coalition in pursuit of a political goal — ending legal abortion — created a juggernaut that has now overturned Roe v. Wade, a five-decades-old Supreme Court ruling that gave women a constitutional right to abortion.

Friday’s opinion by Justice Samuel Alito in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization is the crowning achievement of a conservative Christian drive to reshape American society to hew more closely to the traditional sexual and gender values they espouse.

The ruling upholds a Mississippi law that bans most abortions after 15 weeks and essentially eliminates a woman’s right to privacy guaranteed in Roe. While it does not ban abortion, it leaves it up to states to decide how abortion should be regulated.

It is exactly the ruling the religious right has been waiting for since setting their sights on the Supreme Court after other legislative avenues failed.

This mighty coalition comprising mostly conservative Catholics, evangelical Christians and Mormons did not ground its aims in theological language but instead in the language of human rights. Its advocates saw themselves as defending the inalienable right to life of a defenseless minority: the fetus, or to use their term, the unborn.

“It wasn’t built out of an effort to bridge religious differences,” said Jennifer Holland, the author of “Tiny You: A Western History of the Anti-Abortion Movement” and a history professor at the University of Oklahoma. “Religious people built coalitions because the politics led them there.”

The first mainstays of the movement were Catholics, who had opposed abortion long before the 1973 ruling made it legal.

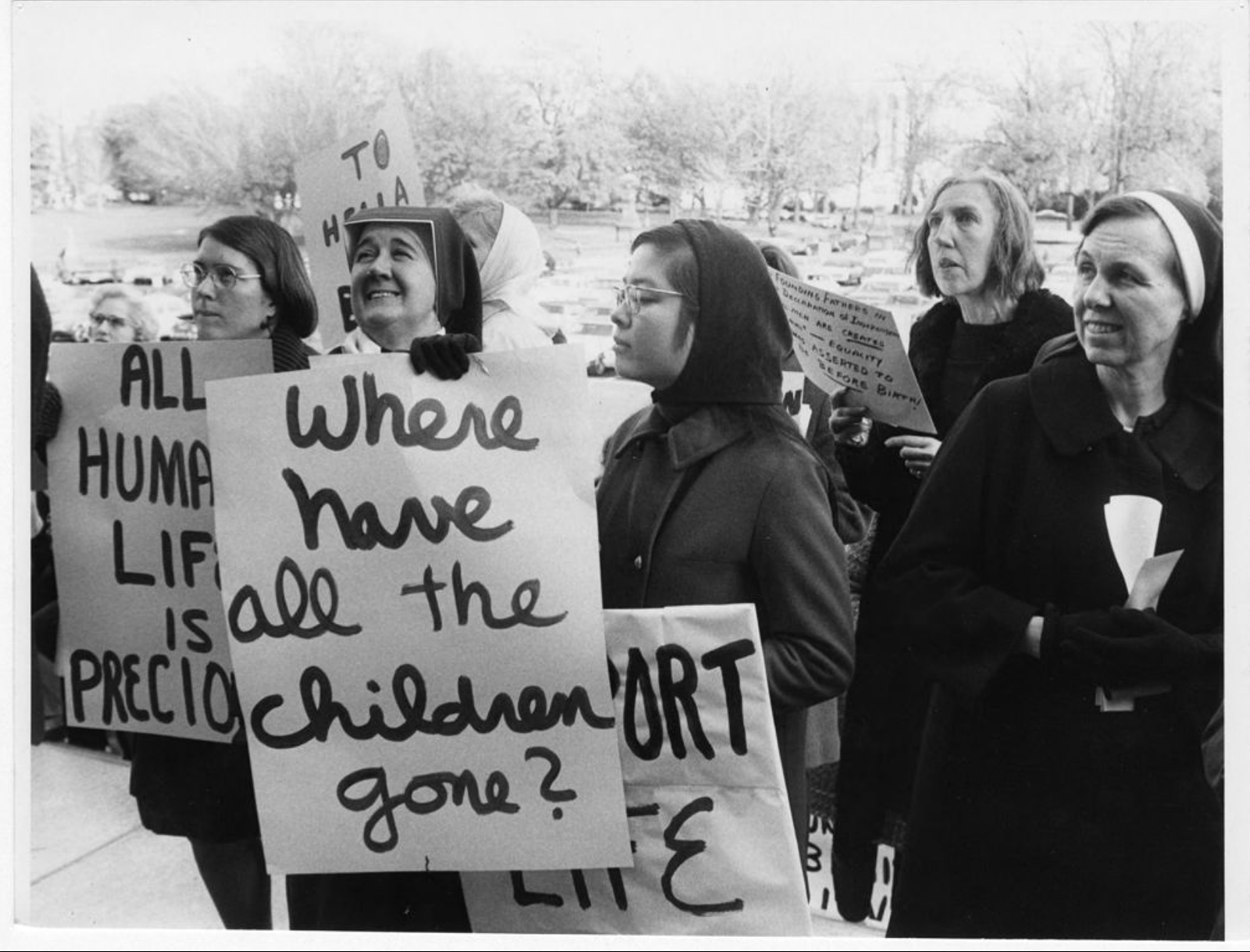

Several nuns from Maryland communities carry placards as they participate in an anti-abortion rally at the east front of the Capitol Building in November 1971, in Washington. RNS archive photo. Photo courtesy of the Presbyterian Historical Society.

Protestant views on the issue were still evolving.

“Once upon a time, Protestants had been allowed to have a wide range of views around abortion, and it really wasn’t perceived to be a religious issue,” said R. Marie Griffith, who oversees the John C. Danforth Center on Religion and Politics at Washington University in St. Louis.

Liberal Protestants and Jewish leaders were fierce advocates for abortion rights, forming groups such as the Clergy Consultation Service to help women receive safe abortions.

Conservative Protestants espoused more complex views. In 1971, the Southern Baptist Convention passed a resolution expressing general opposition to abortion but outlining exceptions. They affirmed that resolution again in 1974, calling it a “middle ground” between the extreme of abortion on demand and the opposite extreme of all abortion as murder.

RELATED: Dobbs decision and fall of Roe met with rejoicing, dismay from faith groups

Daniel K. Williams, a professor of history at the University of West Georgia, noted that Foy Valentine, who directed in the 1970s what would become the public policy arm of the Southern Baptist Convention, even supported the Religious Coalition for Abortion Rights, now known as the Religious Coalition for Reproductive Choice.

Evangelist Billy Graham and Christianity Today’s first editor, Carl Henry, both opposed abortion on demand but supported exceptions for rape, incest and the life and health of the mother.

But Roe v. Wade, was a powerful turning point. After Roe, “the conservative Protestant position on abortion became Catholicized,” said Griffith, author of “Moral Combat: How Sex Divided American Christians and Fractured American Politics.”

“Conservative Protestants take on what had been the consistent Catholic view, which was much more that abortion is a sin.”

The March for Life in Washington, D.C., on Jan. 27, 2017. RNS photo by Adelle M. Banks

Only decades earlier, these Catholics and Protestants eyed each other with suspicion, each defending their exclusive claims to Christian orthodoxy.

Now Catholics such as Phyllis Schlafly and evangelicals such as Jerry Falwell were working on common goals — opposing feminism, the Equal Rights Amendment and LGBTQ rights.

Abortion, as well as what they saw as the breakdown of the traditional family, allowed them to overcome those differences.

“Abortion was what brought us together,” said Ralph Reed, executive director of the Christian Coalition during the early 1990s. “But it was about a broader phenomenon. We believed the darkness in the culture had become so pervasive.”

On the grassroots level, the National Right to Life Committee, founded by the American Catholic bishops in 1968 as the “Right to Life League,” was the hub that drew many people in. Seeking to expand its reach, the NRLC reorganized as an independent organization in 1973, and evangelicals slowly began to adopt its political strategy and public outreach techniques.

An early adopter was Robert Holbrook, a Baptist pastor from Texas who founded Baptists for Life in 1973. He repurposed anti-abortion ads from the National Right to Life Committee but removed the organization’s name before placing the ads in Baptist newspapers lest Baptists object to being fed Catholic doctrine.

“One of the things he says, make use of the materials but remove any Catholic references; put your name on top of it,” said Neil J. Young, an independent scholar and podcaster and author of “We Gather Together: The Religious Right and the Problem of Interfaith Politics.”

The growing split in American politics was reflected in American religion, often within denominations.

“In the Southern Baptist Convention, the two sides did dialogue with each other, though not very politely, ultimately resulting in a conservative takeover of the denomination,” Williams said. “That was one issue among several that contributed to the sea change in the denominational leadership in the SBC in 1979.”

Opposition to abortion spanned many strategies. Early on there was the Human Life Amendment to the Constitution, an effort to effectively overturn Roe by making abortion explicitly anti-constitutional. Multiple iterations of the amendment were drafted but never gained traction in the states or in Congress.

Frustrated with the growing number of abortions and the lack of any legislative solution, some anti-abortion campaigners took up civil disobedience. In 1986, Randall Terry, the founder of Operation Rescue, was arrested for chaining himself to a sink at an abortion clinic. Members of his group were frequently arrested for protesting outside women’s clinics, where they displayed blown-up photos of fetuses or physically tried to block the clinic entrance. Raised a Pentecostal, Terry converted to Catholicism in 2006.

Nonviolent protests on occasion became violent. In 2003, one of Terry’s most ardent followers, James E. Kopp, was charged with the 1998 killing of Barnett Slepian, a physician who provided abortions in the Buffalo, New York, area.

Far more common among religious groups were Right to Life Sundays, a Catholic initiative that sought to dedicate a Sunday each year to abortion with sermons and Sunday school lessons on the need to fight abortion. Evangelical churches widely copied the strategy.

By the 1990s, as evangelical opposition to abortion hardened, discussion about exceptions to a hoped-for ban on abortion fell away. Today, many evangelicals, particularly those who call themselves “abolitionists,” oppose any exception.

In this Nov. 30, 2005, file photo, an anti-abortion demonstrator stands next to an abortion-rights supporter outside the U.S. Supreme Court in Washington. (AP Photo/Manuel Balce Ceneta)

By the early 2000s, opposition to abortion had grown to such a fevered pitch that it became a litmus test for faith itself, a kind of shorthand in certain circles for whether a person could be considered Christian.

After Roe, the most significant turn in the abortion debate was the political shift among conservative Christians — Catholics and evangelicals alike — toward the Republican Party. Each had their own reasons for their defection from a historic affinity with the Democrats, but abortion — particularly anger over President Jimmy Carter’s support for legal abortion — cemented both groups’ newfound allegiance with the GOP.

Ronald Reagan, Carter’s opponent in the 1980 presidential election, courted people of conservative faith assiduously, and they responded. The Rev. Jerry Falwell, the leader of the newly founded Moral Majority, claimed his organization had registered 4 million first-time voters for Reagan. In every presidential election since, the anti-abortion alliance voted Republican.

It was under Reagan that the anti-abortion movement set its sights on flipping the Supreme Court to a majority that would be willing to reexamine Roe.

Rob Schenck, an evangelical who once prominently opposed abortion, saw the politics behind the anti-abortion movement as misguided.

“I call that our deal with the devil,” said Schenck, who now supports abortion rights. “We sold our soul to the Republican Party. They got silence from us on other policy initiatives and eventually our current complicity. Very rapidly the movement became less about women in crisis pregnancies and their babies and more and more about political victories and eventually the exercise of power.”

Depending on Roe as the bulwark against the combined forces of the religious right and Republicans meant relying on the unpredictable longevity of the court’s justices and the increasingly contentious confirmation process in the Senate. When Majority Leader Mitch McConnell refused to hold hearings in 2016 for President Obama’s proposed replacement for Justice Antonin Scalia, he rejiggered a high-stakes political procedure that had relied largely on fate to keep the balance intact.

President Trump speaks via a live feed to anti-abortion activists as they rally on the National Mall in Washington, on Jan. 19, 2018, during the annual March for Life. (AP Photo/Andrew Harnik)

Running for president that year, Donald Trump issued a list of 21 potential nominees to the Supreme Court, all staunch conservatives who were skeptical of unenumerated rights like the right to privacy, which lay at the center of Justice Harry Blackmun’s 1973 Roe ruling.

“Trump was the first person to ever run for president to say, ‘Here’s the list. I’m going to choose (jurists) from this list,’” said Reed. “It was a specific promise.”

Some 81% of evangelicals voted for Trump, in large part for this reason. The deal the GOP had made going back to the 1980s finally came to fruition.

Supreme Court Justices Brett Kavanaugh, John Roberts, Clarence Thomas and Amy Coney Barrett all joined Samuel Alito in concurring in Dobbs. All are Republican nominees.