(RNS) — When Anne Klaeysen first applied to be the humanist chaplain at Adelphi University in Garden City, New York, in 2002, the deans interviewing her went straight to the point: “The other chaplains want to know,” they said, “if you’re a religion-hating atheist.”

Klaeysen readily assured them that no, she didn’t hate religion, but wasn’t surprised by the assumption. At the time, humanist chaplains on American campuses were practically unheard of, and those who had heard of them were usually puzzled by a chaplain who didn’t believe in God.

Klaeysen, who served at Adelphi for almost a decade, is now the humanist chaplain at both Columbia University and New York University. She’s still just one of a handful of humanist chaplains at American universities, but the number is growing as Gen Z comes to dominate campuses. According to a 2020 survey from Springtide Research Institute, some 40% of the current generation of college students are not affiliated with a religion.

“The nonreligious have as much of, or more of, a need for meaning, purpose and community as anybody else,” said Greg Epstein, humanist chaplain at Harvard University and Massachusetts Institute of Technology. “This is an enormous number of young people searching for answers to the question of how to build a good life, how to build a good community.”

Just as Muslim or Buddhist students are most likely to seek guidance from a chaplain who shares their faith, nonreligious students will probably feel more comfortable bringing inquiries about meaning and morality to nontheists.

At Tufts University in Medford, Massachusetts, where more than 40% of students already identify as atheist, agnostic or nonreligious, humanist chaplain Anthony Cruz Pantojas explained in an email that hiring chaplains like them “creates a fluid space to explore both secular and spiritual perspectives.”

Anne Klaeysen, left, and other religious life advisers at Columbia University in New York. Photo courtesy Columbia University

Some of the work for humanist college chaplains is talking to students who are leaving a religious tradition behind. Klaeysen recalls a formerly Mormon student wanting to know how much to disclose about her lack of faith to her family over winter break. Instead of doling out advice, Klaeysen asked the student what she believed in and what had changed, in the hopes of helping her clarify her beliefs before making a proclamation to her parents.

“It’s about deep, empathetic, nonjudgmental listening,” explained Klaeysen, who goes by “religious life adviser” or “spiritual life adviser” to avoid the religious connotations of “chaplain.” “And there’s very often a presenting issue, what caused them to send the email, and then there’s also the underlying issue that you’re really listening to — what’s vibrating.”

Vanessa Gomez Brake. Photo courtesy USC

Much of the time, like any chaplain, they are faced not with religious questions at all but counsel students who feel lost. At the University of Southern California in Los Angeles, Vanessa Gomez Brake, a humanist chaplain and associate dean of religious and spiritual life, says many of her students are grappling with isolation.

“Because these students have grown up online, the quality of their relationships are different,” said Gomez Brake. “Not to say they don’t have meaningful and close friendships, it’s just that they have many more friendships that are not meaningful.”

Standing outside established religion, humanists are prepared to handle Gen Z’s tendency to fashion a highly personal spiritual practice out of an assortment of faiths and spiritual traditions. Gomez Brake recently ran into a student wearing a gemstone necklace to ward off anxiety.

“She donned this piece of jewelry to invoke what she needed to engage her finals,” said Gomez Brake. “For some people, it may be putting on your cross necklace every day and thanking God for the day, but for this woman it was engaging these gemstones to get her in the right head space and body space to do what she needed to do.”

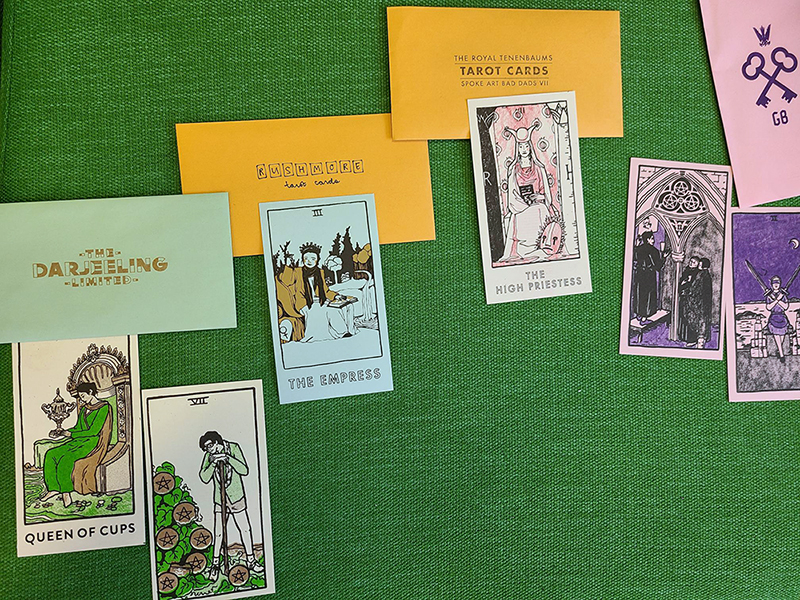

In Gomez Brake’s office, full of brightly colored furniture and art meant to foster conversation, she also keeps a deck of Wes Anderson-themed tarot cards on hand.

“It ends up being an aid that’s unpacking what’s of interest to them, but also making meaningful connections,” said Gomez Brake. “I don’t believe in the supernatural stuff that tarot connects with, but imagery is powerful and can elicit certain reflection that a blank, clinical space cannot.”

Wes Anderson-themed tarot cards used by Vanessa Gomez Brake at the University of Southern California in Los Angeles. Photo courtesy Vanessa Gomez Brake

Gomez Brake will help students devise rituals to address challenges, such as a bedtime ritual she created with a student who was having trouble sleeping. It involved putting away technology, sipping a warm beverage and treating the bed as a cherished space free of homework and electronics. The student purchased a new duvet cover to mark his bed as a place of sacred rest.

RELATED: What Harvard’s humanist chaplain shows about atheism in America

For a college generation that takes social justice seriously, humanists, like other chaplains today, also spend much of their time organizing, sign painting and marching about the environment and inequity.

Nina Lytton. Photo by Susan R. Symonds/Infinity Portrait Design

“Student activists are troubled by the state of the world, and frustrated and angry because they are discovering their boundaries about what they are willing to say yes to, and where they have to draw the line,” said Nina Lytton, an interfaith chaplain at MIT who is also a humanist. “I find that sometimes involves asking, how could God allow this?”

The best way to reach students, said Lytton, is on foot at protests, student centers or campus coffee shops. “My office is the campus, and what I take with me for chaplaincy, I always have Kleenex, snacks, cash and Band-Aids,” said Lytton.

“You have to get out there and walk around. It is clear who is in distress. You can see it. I go toward the distress, and that includes moral distress. And I’m not looking for souls to convert. I’m looking for situations I can help to ease.”

When Ukrainian and Russian students found themselves this spring suddenly grappling with the realities of war, Lytton and MIT’s head chaplain, the Rev. Thea Keith-Lucas, hosted a candlelit vigil, with cookies, hot cocoa and tables where activists and allies gathered to design action plans.

“These people became activists. This was thrust upon them. We didn’t sit in our office waiting for them to call us. To me, that’s not how it works,” said Lytton.

Accompanying students in their concerns side by side with their fellow chaplains, humanist chaplains’ seeming contradictions dissolve in the work. “We, as colleagues, can model the ways we seek common ground together,” said Klaeysen.

Students pet dogs during an event sponsored by USC’s Office of Religious and Spiritual Life in Los Angeles. Photo courtesy Vanessa Gomez Brake

Increasingly as institutionalized religion continues to fall out of style, Gomez Brake warns that it is the theistic chaplaincy programs that will need to adapt.

“I think many offices of religion and spiritual life are making themselves obsolete because they only work within the confines of religious traditional worldview,” she said. To remain relevant, Gomez Brake believes universities will need to provide more offerings geared toward spiritual wellness more generally. Part of that shift will require an approach that humanists are quite comfortable with.

RELATED: Campus ministries, counselors join to tackle mental health