Teaching American History is proud to introduce our newest volume in the Core Document Collection, The Judiciary. Edited by Joshua Dunn, this volume presents an array of views on the role that the courts should play in American life and how they should interpret the Constitution and our laws.

Judicial Review vs. Judicial Supremacy

No court exercises more power than the Supreme Court of the United States. That is not because it is the highest court of the most powerful nation in the world—although it is. Instead, it is because no court exercises more political power within its political order than the U.S. Supreme Court. The reason is, of course, the power of judicial review, or perhaps more accurately judicial supremacy, the idea that the Supreme Court is the final interpreter of the Constitution. It is important to distinguish between judicial review and judicial supremacy. Judicial review as initially conceived was a limited power that allowed the Court to avoid being controlled by what it regarded as the unconstitutional decisions of other branches. Properly read, this is the argument of Chief Justice Marshall in Marbury v. Madison. But this power did not extend to control over other branches. It did not allow the Court to dictate to other branches the limits of their constitutional powers. Judicial review eventually came to mean judicial supremacy, the notion that the Supreme Court is the ultimate and final interpreter of the Constitution and can indeed tell the other branches what they can and cannot do constitutionally. This power has always rested uneasily with principles of self-government. The most common attempt to defend judicial review contends that ratifying the Constitution was the most important act of self-government by the American people. Thus, when the Court strikes down a law as unconstitutional, it is defending the first act of self-government by the people.

Smithsonian Institution; transfer from the National Gallery of Art; gift of the A.W. Mellon Educational and Charitable Trust, 1942.

But even if one accepts this defense of judicial review, other questions arise. Why should the Supreme Court be the final interpreter of the Constitution? The Constitution does not say that the Supreme Court is the guardian of the Constitution. In fact, the Constitution requires that the president and senators and representatives, as well as the members of the state legislatures and state executive and judicial officers, must also take an oath to uphold the Constitution (Article II, section 1; Article VI). Thus, through its structure of separation of powers and the duties it imposes on all the branches, one could argue that all three branches of the federal government have both the power and the duty to interpret the Constitution, an idea known as departmentalism. And if the Court is the supreme interpreter of the Constitution, does that not inherently make the decisions of the Court more important than the Constitution itself? As well, what guarantee is there that the Supreme Court will accurately interpret the document? And if the Court can impose its own preferences on the country under the guise of interpretation, does that also not implicitly empower the Court to amend the Constitution, undermining the constitutional authority of the people to do this through the amendment processes laid out in Article V?

The Debate over the Role of the Supreme Court

Disputes over Supreme Court nominations over the past four decades have made these questions particularly salient. However, Americans have been debating them since before the Constitution was ratified. The Judiciary presents many of the core documents surrounding this debate over the power of the Supreme Court and its role in American self-government. The Anti-Federalists found Article III, which created the Supreme Court and gave Congress the authority to create lower federal courts, deeply alarming. Brutus along with other Anti-Federalists predicted that even though the Constitution did not confer final interpretive authority on the Supreme Court, that would nevertheless become the accepted practice, and justices would use this power to impose their policy or political preferences under the guise of interpretation. Although Alexander Hamilton’s famous Federalist 78 (Document 2) attempted to allay those fears about judicial power, it is fair to say that Brutus’ prediction about judicial supremacy came true. Within fifty years Daniel Webster (Document 7) was equating disagreeing with a constitutional decision of the Supreme Court with an invitation to anarchy. Later, Abraham Lincoln (Document 8) contended that accepting the Court as ultimate interpreter of the Constitution, as Stephen Douglas said Americans must do (Document 9), meant that opponents of slavery would have to submit to the reasoning of the Court’s Dred Scott decision, which held that free blacks could never be citizens. Whether the Supreme Court should exercise the power of judicial review to strike down legislation because the justices think it is bad policy has also been a consistent source of controversy throughout its history. Brutus (Document 1) envisioned justices doing this, as did the Court in Plessy v. Ferguson (Document 10) and Lochner v. New York (Document 11).

Limits on Judicial Power

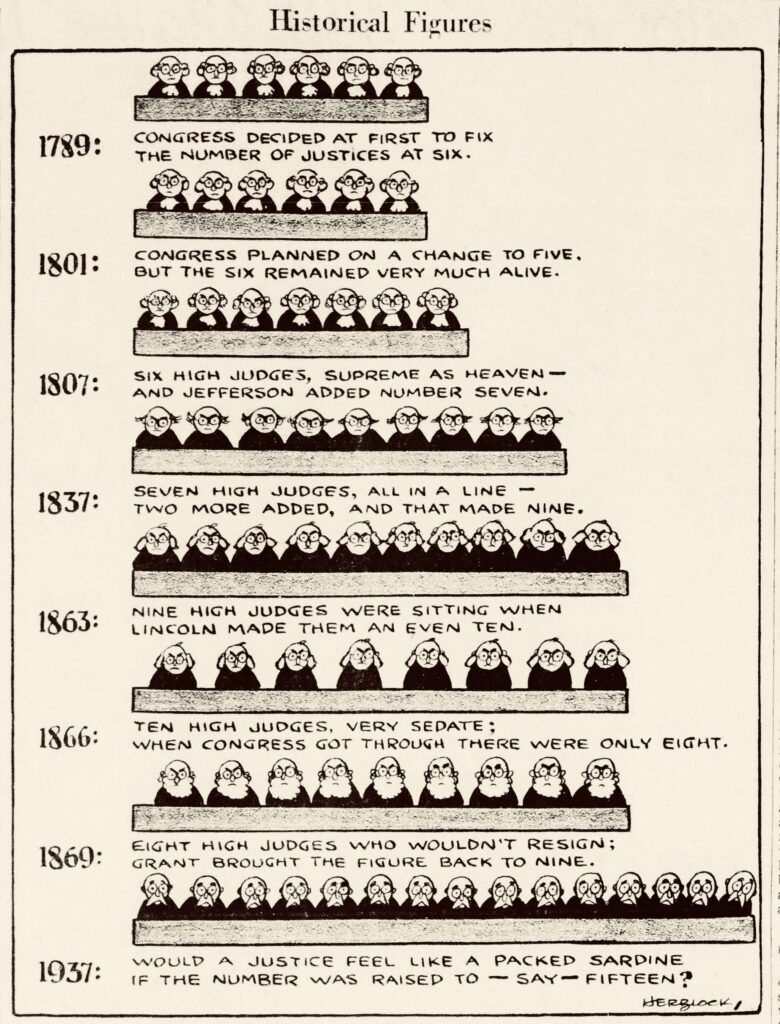

As the Court’s power developed and expanded, other institutions tried to impose limits, most significantly in Franklin Roosevelt’s court-packing plan (Document 12). While Congress decisively rejected that proposal (Document 13), more recently the idea of expanding the Court to change its ideological composition—that is, to change it to reach desired political outcomes—has been resuscitated in response to Republican senators delaying the replacement of Antonin Scalia and accelerating the replacement of Ruth Bader Ginsburg. But these conflicts really point to a more fundamental conflict over how the Constitution should be interpreted. In response to decisions that struck them as untethered from the text, conservatives have argued that the only way to reconcile judicial power with republican self-government is for judges to interpret the Constitution according to its original meaning (Documents 18 and 21). Originalism, initially derided by legal and political elites, has now become so entrenched that even some progressive constitutional scholars have declared, “We’re all originalists now.” Ironically, it now appears that some on the right have lost their faith in originalism and are offering interpretive arguments that seem more resonant with the living constitutionalism of liberal stalwarts like William Brennan (Documents 19 and 28).

The debate over judicial power has also led to other debates over judicial representation. For much of the Supreme Court’s history presidents tried to preserve geographic diversity by ensuring that the Court always included justices from different regions of the country. Today that concern has shifted to what some have called “identity politics”—how judges’ race and sex might affect their decisions. Should those aspects of personal identity matter when judges decide cases? Will judges from particular ethnic backgrounds make better judges, as Justice Sotomayor once contended (Document 26)? If so, then what are the implications of that for principles of constitutional equality and the rule of law?