Growing up in a house of Cuban exiles, there are certain things you become accustomed to—strong coffee, plantains, and an endless history lesson on US-Cuba relations. From an early age, I was versed in the cruelties of Castro and Che, the last stand of Assault Brigade 2506, and the tragedy of the Cuban Missile Crisis. With the 60th anniversary of the Cuban Missile Crisis upon us, everyone the world over can look back with relief that the world did not succumb to thermonuclear war. A great many Americans also look back with respect at the resolve of President Kennedy, whom they believe stared down Soviet aggression in our own backyard. But for Cuban exiles like my grandfather, those two weeks in October 1962 were summed up quite differently. He always declared unequivocally that “Khrushchev won.” With more than half a century now separating us from that terrifying fortnight and with so many of that generation passing on each day, it is appropriate to look back at the origins of the crisis and what it may mean moving forward in the 21st century.

The Cuban Missile Crisis: The Basics

Narrowly speaking, the Cuban Missile Crisis was a tense standoff between the United States and the Soviet Union for about 13 days in October 1962. Though there were vague Soviet assurances of defense for Cuba dating back to 1960, and direct warning signs going back to the summer of 1962, the crisis became immediately apparent on 15 October when CIA analysts confirmed the presence of ballistic missiles from photographs taken a day earlier by a U-2 spy plane surveilling Cuba. This set off a flurry of military and intelligence activity, culminating in the formation of a special advisory group, as well as meetings of the newly formed Executive Committee of the National Security Council (EXCOMM), which Kennedy convened to assess possible responses to the installation of the Soviet missiles in Cuba. Despite significant pressure from top advisors to launch an all-out blitz from the air on Cuban airfields and the missile sites, Kennedy ultimately sided with those who advised a cautious, but deliberate action—a naval blockade of Cuba to be dubbed “quarantine.”

On 22 October, millions worldwide gasped when President Kennedy announced on television the presence of Soviet missiles in Cuba and the United States’ determination to see them removed at any cost. The following day, 23 October, Kennedy issued Proclamation 3504, the naval blockade of Cuba in all but name. Soviet Premier Khrushchev responded by sending ships and submarines seemingly to challenge the US Navy. On 25 October, the majority of Soviet ships turned back before breaching the quarantine line, but an oil tanker continued onward and the US Navy allowed it to pass.

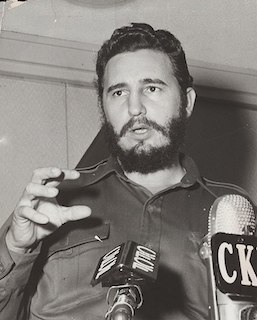

Over the next two days, the crisis came to a head. Cuba’s dictator, Fidel Castro, suggested the USSR launch a nuclear strike on the US, and a U-2 spy plane was shot down over Cuba, killing the pilot. With the two superpowers seemingly poised at the the brink of nuclear war, and countless people preparing their fallout shelters for the expected nuclear apocalypse, Khrushchev wrote to Kennedy appealing for a peaceful resolution. He proposed that, if Kennedy promised not to invade Cuba and topple the Castro regime, no further Soviet arms would be sent to Cuba. Kennedy and Khrushchev came to a secret agreement. The Soviets agreed to remove the missiles from Cuba and leave Turkey alone in exchange for US agreement to remove missiles from Turkey and leave Cuba alone. On 28 October, the bated breath of the world was exhaled slowly as the crisis was resolved. Public declarations outlining parts of the secret agreement between Kennedy and Khrushchev were released in a manner that allowed both leaders to declare victory.

This peaceful resolution of what is generally considered the most dangerous nuclear confrontation ever between the US and USSR was, and continues to be, hailed as a moment of triumph for the Kennedy administration—and a moment of massive relief for the world. How, then, in the eyes of Cuban exiles like my grandfather and father, did Khrushchev win? To understand this perspective, we must first take a brief look backward at the history of relations between the US and Cuba.

History of US Involvement in Cuba

Monroe Doctrine

Within 50 years of independence, the United States had established itself as a regional or hemispheric power through successful naval operations against European and North African powers and by repelling a British invasion in the War of 1812. President Monroe boldly claimed in his seventh annual message to Congress (1823) that the US would resist all European imperialist ambitions in the Western Hemisphere and would consider European expansion in the hemisphere as an act of war against the US. Shockingly, European powers abided by the Monroe Doctrine. The US entered its own period of imperialistic expansion a little over a half century later. Cuba was swept up in this expansion during the Spanish-American War, a war in which future president Teddy Roosevelt played a pivotal role. Several years later, President Teddy Roosevelt expanded the Monroe Doctrine and asserted a general “police power” over the Caribbean basin. Between the Roosevelt Corollary and the Platt Amendment, the US made it clear that while Cuba was to remain a separate country, it was very much under the US sphere of influence.

Cuban Independence

The first several decades of Cuban independence were, to put it mildly, fraught with political instability, incompetence, and corruption. A degree of stability, if nothing else, came with the rise of US-backed strongman Fulgencio Batista, but the corruption and repression of his regime was so intolerable that Fidel Castro was able to topple the Cuban government with a few thousand armed supporters in late 1958 and early 1959. Many Cuban nationalists were initially supportive of this regime change. They suffered under Batista’s cruel regime and bristled at the US government’s consistent meddling in Cuban affairs via the Batista regime. However, when Castro revealed himself to be a Marxist-Leninist, a great many Cubans reacted in horror. They actively hoped for US intervention. Future exiles like those in my family could not conceive a reality in which the US would allow a communist regime a scant 90 miles from its coast. Even following the disastrous Bay of Pigs invasion (1961), Cubans and Cuban expatriates in the US remained convinced that the US would remove Castro’s increasingly oppressive regime. The death knell of that hope came at the conclusion of the Cuban Missile Crisis, when President Kennedy promised Premier Khrushchev that the US would not invade Cuba. The Cuban exile community in the US knew then that they would likely never walk as freemen in Cuba again. Castro had won because Khrushchev had won.

Communist Cuba

For the US, the price of possibly avoiding nuclear war was allowing Cuba to remain communist. The theoretical threat to the US was a very tangible threat to the wellbeing of millions of Cubans. The Cuban Missile Crisis and its resolution also called into question just how far the US would go in confronting and containing the Soviet threat for the remainder of the Cold War.

Though the Cold War is now long over, the consequences of the Cuban Missile Crisis remain a stark reminder of the perils of overseas entanglements and adventures first voiced by President Washington in his Farewell Address[1] and most recently experienced last year in Afghanistan. Regardless of whether one perceives the Cuban Missile Crisis as Kennedy’s or as Khrushchev’s victory, it is important that no one ever forget the very real human costs of such conflicts, especially as the crisis increasingly fades from living memory.

Greg Balan is a 2016 James Madison Fellow for Florida, the 2022 State History Teacher of the Year for the Florida State Society of the Daughters of the American Revolution, and a proud MAHG graduate.

Interested in learning more about the history of American intervention? Join us for our free foreign policy webinars on November 16th, December 14th and January 18th