The following is an excerpt of our latest CDC volume, Native Americans. Written by volume editor Jace Weaver, it describes the scope and purpose of this particular volume.

The utmost good faith shall always be observed toward the Indians; their lands and property shall never be taken from them without their consent; and, in their property, rights, and liberty, they shall never be invaded or disturbed, unless in just and lawful wars authorized by Congress….

Northwest Ordinance (1787)

Settlers in North America, be they the Vikings, the French, or the English, followed the same pattern with regard to the Indigenous peoples they encountered: first cooperation, then conflict. Even the Spanish, whose reputation for unrelenting cruelty preceded them, were initially treated with hospitality by the Pueblos in New Mexico.

The young American Republic promised fair dealing with the original sovereigns of the land it occupied. It professed to have a trust obligation toward them. Despite periodic attempts to live up to these responsibilities, its efforts were hampered by fundamental misunderstandings of Native cultures and a paternalistic attitude that non-Indians knew what was best for Native Americans. The old pattern was replicated. This volume documents a repeated cycle of conflict and resistance. There were, however, non-Natives who saw things clearly. William Tecumseh Sherman, who prosecuted the Indian Wars in the West with the same “hard-war” methods he employed during the Civil War, was among those who were gimlet-eyed about U.S. Indian affairs. His mordant observations dot this book. (The irony in Sherman’s middle name is obvious; his father was an admirer of the great Shawnee leader.)

Dispossession and loss are major themes in this volume. At the time Columbus arrived, best estimates are that there were between twelve and fifteen million Indigenous persons in the territory that is today the United States. This population reached its nadir in 1900, when the U.S. Census recorded just 237,000 American Indians. This tremendous population loss was not so much due to cruel treatment or warfare—though both these occurred—but to a dramatic demographic crash from “virgin soil plagues”—diseases Europeans brought with them to which the Native population had no natural immunities. The biggest killer was smallpox, but the list also includes measles, mumps, rubella, pertussis, chicken pox, and influenza.

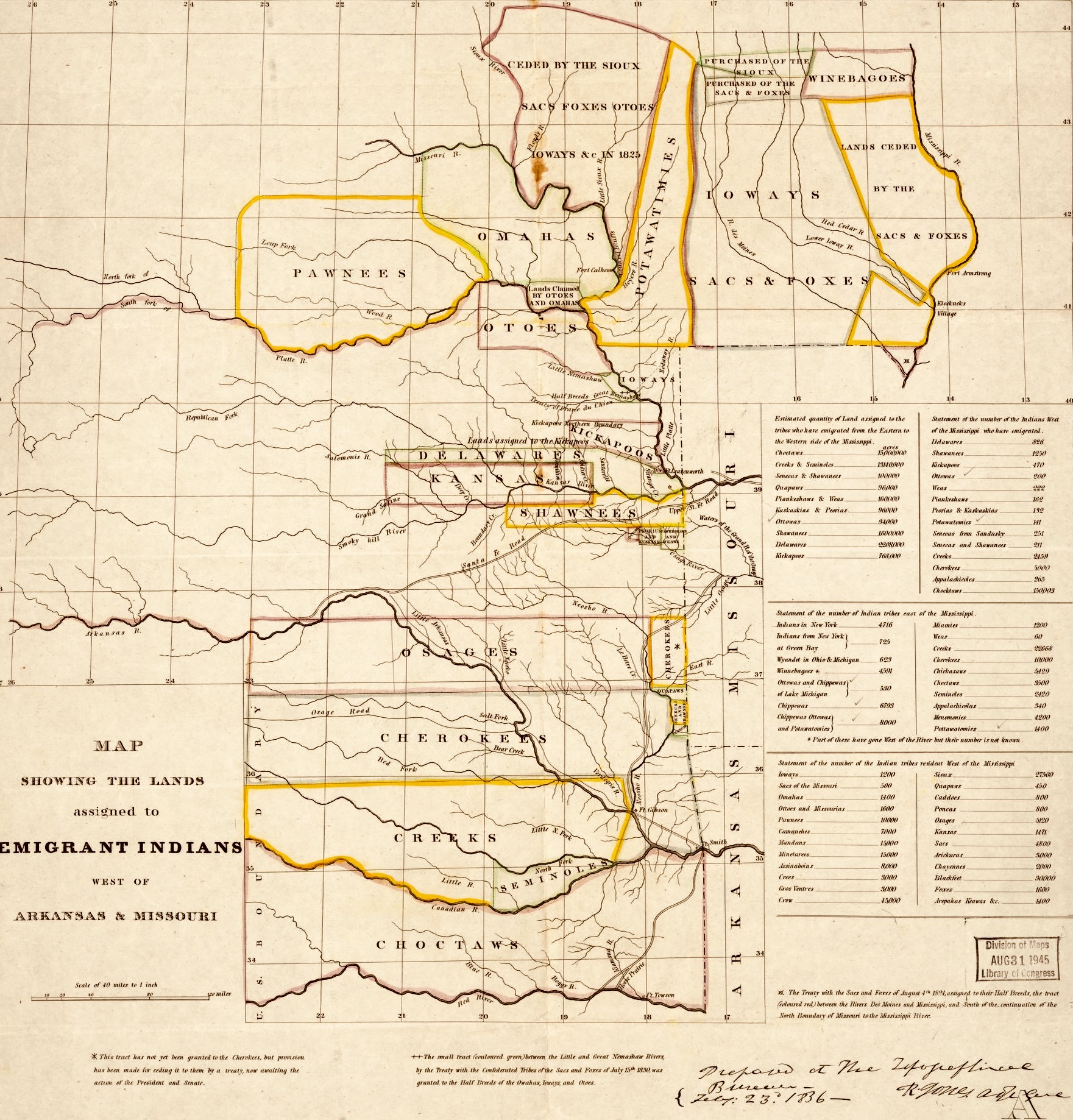

This book seeks to cover almost five hundred years of American Indian history from Jonas Michaëlius’ letter in 1628 to the Supreme Court’s 2020 decision in McGirt v. Oklahoma, which ruled that much of that state remained Indian land or reservations because of treaties signed between Indian tribes and the U.S. government. From the Royal Proclamation of 1763 to the present day, government policy has constrained Native life. Yet despite these actions, Natives have always sought to live their lives on their own terms and to maintain the sovereignty of tribes as nations-within-a-nation, separate sovereigns in the U.S. federal system. For its part, federal policy has always vacillated between wanting to “civilize” and assimilate Indians and encouraging self-government and self-determination.

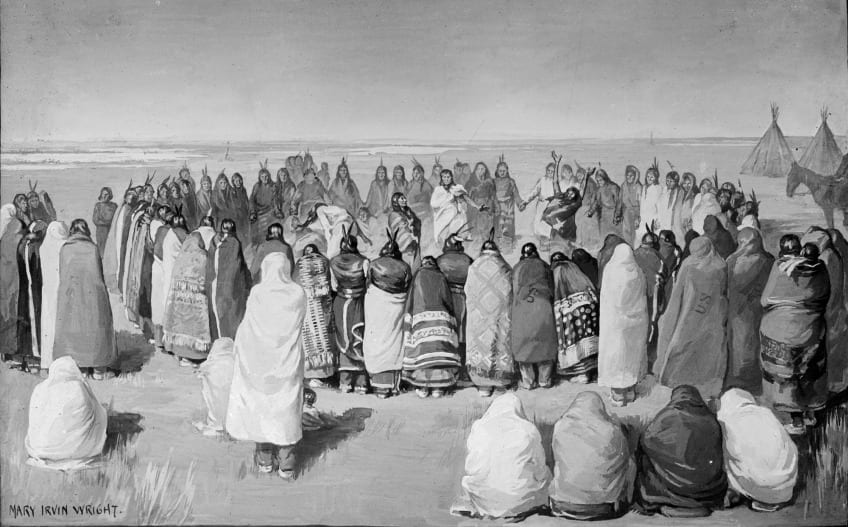

Conflict and warfare are major themes herein as well, from King Philip’s War in 1675 to the last massacre of Indians in 1911. Aggressive assimilation attempts through education (“education for extinction”) is a thread from the earliest colonization through boarding schools modeled on Richard Henry Pratt’s Carlisle Indian Industrial School. Another thread, however, is Native resistance and protest as manifested in the occupation of Alcatraz Island in 1969 and the Standing Rock Sioux’s opposition to the Dakota Access Pipeline in 2015 and 2016. Traditional Native cultures are religiously based, and religion has played a vital role in Native resistance, especially “raising-up” movements from Pontiac’s Rebellion and Tecumseh’s alliance to the Ghost Dance of 1889–1890.

![[Native American chiefs Frank Seelatse and Chief Jimmy Noah Saluskin of the Yakama tribe posed, full-length portrait, standing, facing front, with the U.S. Capitol behind them]](https://teachingamericanhistory.org/content/uploads/2021/09/native-american-chiefs-frank-seelatse-and-chief-jimmy-noah-saluskin-of-the-1.jpg)

In album: v. 1, p. 9, no. 40873.

Another copy in LOT 12337-1.

I have sought to give pride of place to Indigenous voices (although we must remember that many Native speeches were transcribed by whites). I did not want a dry assemblage of laws, legal decisions, and treaties. Though much of Indian existence has been constrained by such documents, they often do not convey the meaning and importance of events. (Appendix C offers an annotated list of some of the most important documents bearing on the legal status of Indians.) While covering the Indian Wars from King Philip’s War to the last Indian massacre in 1911, resistance to violent assimilationist policies from Christian evangelization, to boarding schools, to Termination and Relocation, and the radical activism of the 1960s and 1970s, I have tried to include surprising documents, such as the Haudenosaunee Confederacy’s declaration of war in 1942, that are not the “usual suspects” often anthologized. Though it includes only forty-six documents, I believe this volume will give both teachers and students plenty to chew on.

American Indians and their ancestors have thousands of years of history on this continent. They have been part of the American story before day one—that is, before the coming of Europeans. It is often glibly said that these first American were not U.S. citizens until 1924. The Indian Citizenship Act of that year, however, was merely a “clean-up” measure covering only roughly the third of Natives who were not yet citizens. American Indians remain today a vital part of the story of the United States, as they always will be.

Note on terms: Many people assume that “Native American” is a more polite and preferred term to “American Indian.” This, however, is not the case. The former, which did not even exist until after World War II, grew out of the urban Native experience that resulted from the federal policy of Termination and Relocation. It is therefore incorrect to refer to any before that time as Native Americans. “American Indian” is an older, more rural, more reservation-based term still in use today. In the last fifteen years, an uppercase “Indigenous” has gained currency. Sometimes, simply “Native” is employed. I use all these terms interchangeably as seems appropriate.

This volume is now available as in hardcopy and as a free download from our bookstore. Get your copy today!