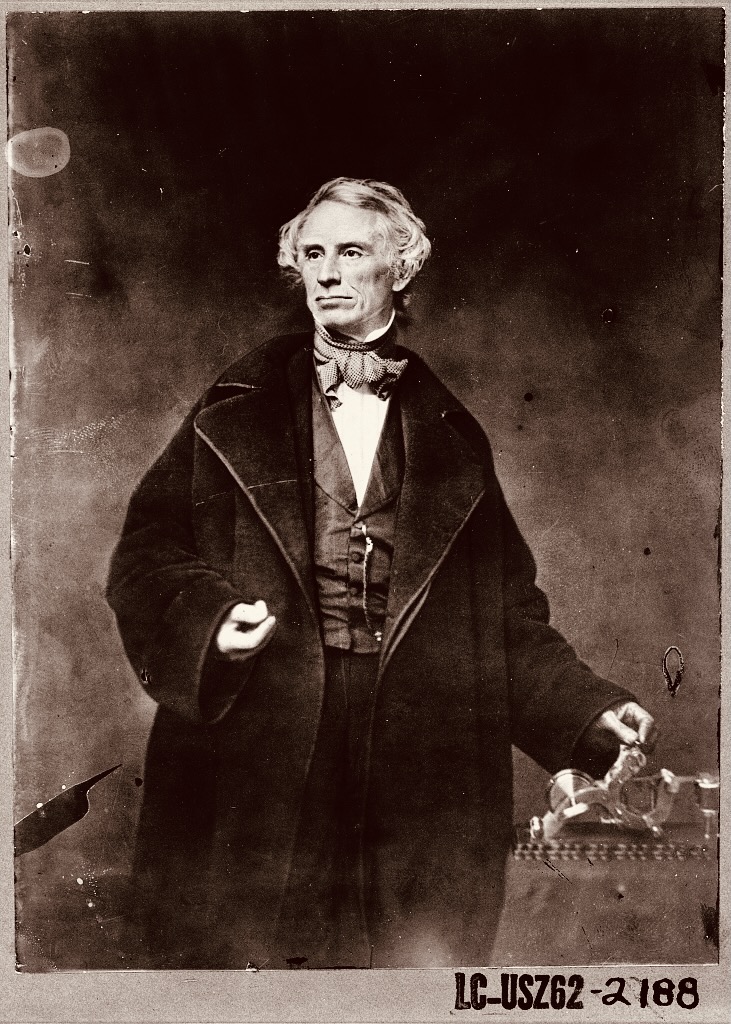

During the early 1980s, I rented a small studio apartment on Capitol Hill, just two blocks from the Library of Congress. I enjoyed the restaurants nearby, and excellent museums were within easy walking distance. Although the restaurants were pricey, the Smithsonian museums on the National Mall were free, so I often wandered their galleries on cold, rainy weekends. While visiting the National Gallery of Art one day, I saw a 6′ x 9′ painting entitled The Gallery of the Louvre and was surprised to learn the artist’s name – Samuel F. B. Morse. Surely, I thought, there could not be two Samuel F.B. Morses. I read the description of the painting. The artist was the same Samuel F.B. Morse (1791–1872) whose simple code of dots and dashes spurred the greatest revolution in communication since Johannes Gutenberg’s invention of the movable-type printing press in the 15th century. I learned that day that Morse was a talented artist. However, his method of electromagnetic communication made Morse rich and famous, not his artistic talent.

The Genesis of an Idea

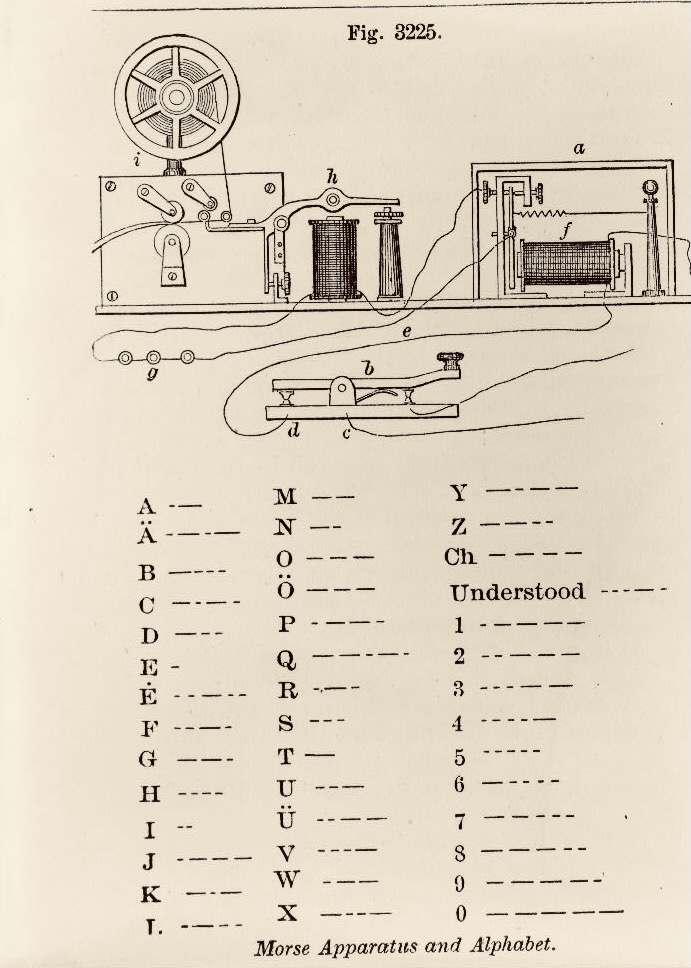

Morse’s inspiration for the telegraph came during a conversation with a fellow passenger on a trans-Atlantic crossing. Initially, Morse hoped to make electrical current “visible” on an electrical circuit. “If the presence of electricity can be made visible,” he said, “I see no reason why intelligence cannot be transmitted instantaneously by electricity.” Later, he realized that a trained operator could quickly transcribe the sounds they heard into readable messages.

Like many other inventors associated with new technologies, such as Robert Fulton and the steam engine and Henry Ford and the automobile, Morse did not invent the telegraph. Instead, he applied existing science and simplified existing technologies, making them more accessible to everyday American life. According to economic historian John Steele Gordon, “the only part of the Morse telegraph system that was entirely original was his marvelously efficient code, which assigns dots and dashes according to the frequency with the letters occur in English.” Even the word “telegraph” did not initially apply to electromagnetic communication. It denominated a signaling system over long distances using flags.

Morse enjoyed success as a portrait artist in America. However, he wanted to paint large panoramic pictures. After being rejected for a commission to paint a mural for the Capitol Rotunda in 1837, he spurned art, turning his attention toward the technical challenge of how to use electric currents, new batteries and electromagnets, and cheaper and improved wire to transmit information over long distances.

Producing the Telegraph

It took Morse several years to secure the financing necessary to test his method. Finally, in 1843, with the help of Congressman F. O. J. Smith, Morse secured $30,000 in federal funds (about 1.2 million in today’s dollars) and began constructing a telegraph line from Washington to Baltimore for a formal test of his system. On May 24, 1844, Morse, seated in the chambers of the United States Supreme Court, tapped the code for his now-famous message: “What Hath God Wrought.” His colleague in Baltimore, Alfred Vail, accurately transcribed Morse’s communication and repeated the message to Morse.

The Telegraph’s Impact

The speed at which this new communication system swept the nation—once proven practical—is astonishing, even to modern Americans so accustomed to rapid technological advances. Two years after Morse’s demonstration, newspaper publishers organized a pony express from New Orleans to Charleston, SC, where news from the Mexican War was telegraphed to New York. By the end of the decade, wires connected most large American cities. In less than a generation, the telegraph reached the west coast, and it crossed the Atlantic Ocean in 1866.

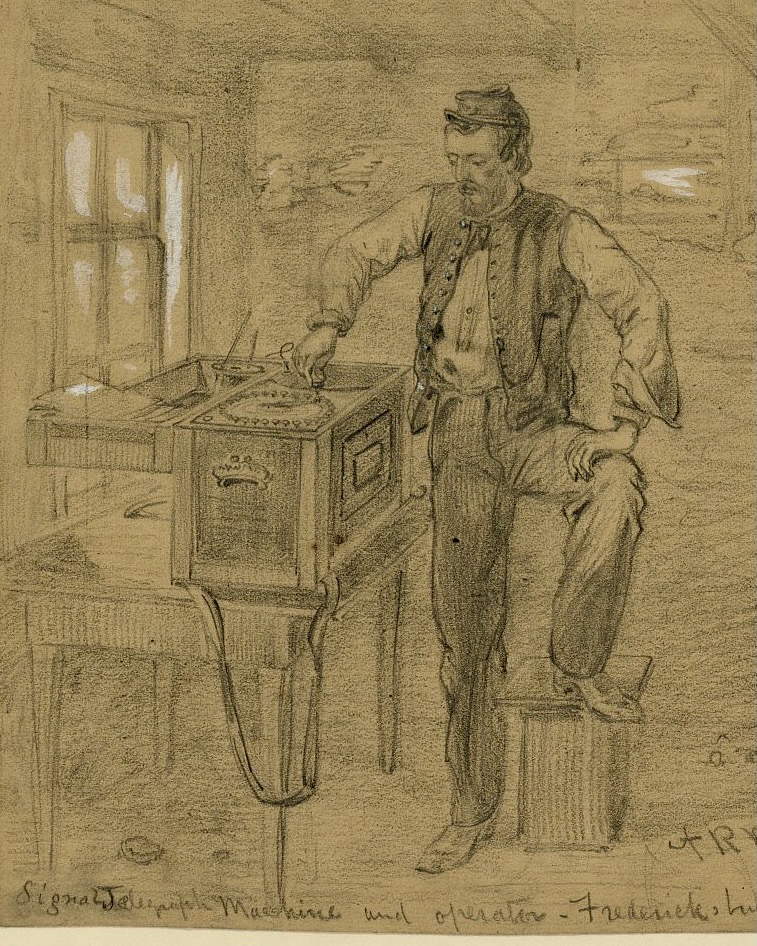

Modern Americans might be less surprised about how the advance in communication impacted American business. Used primarily for commercial purposes—later, the telephone connected Americans socially—the telegraph allowed Wall Street to send more up-to-date information on stock trades. Railroads telegraphed stations down the line to warn conductors of delays and accidents, making travel safer and more predictable. During the Civil War, President Abraham Lincoln spent countless hours in the War Department’s telegraph room awaiting news from the front, enhancing his communication with military commanders in the field. Reporters in the field filed their first-hand accounts of the war’s carnage by telegraph, enabling Americans to experience the horrors of war in a way no previous generation had.

The Communications Revolution

As John Steele Gordon points out in his book, An Empire of Wealth, the telegraph was not the only means of communication rapidly changing in the 19th century. Aided by the telegraph, newspapers were changing the way Americans learned about events and shopped for new products. The New York Herald, published by Scottish immigrant James Gordon Bennett used the telegraph and new, faster, steam-powered rotary presses to change the business of gathering and reporting the news into something like modern media outlets. Unlike previous American newspapers, the Herald was officially non-partisan in its news articles. It was the first to cover weather and sports regularly. The Herald covered sensational crime stories that other newspapers avoided out of concerns for “respectability.” Bennett took full advantage of the telegraph. He fought Congress for access to news from D.C, thus establishing the roots of a Washington news bureau.

The Herald‘s success and that of rival newspapers led the editors of the North American Review to proclaim in 1866 that “The daily newspaper is one of those things which are rooted in the necessities of modern civilization.” The newspaper industry, buoyed by newer and faster printing presses, and access to telegraph reports filed from any town in America, found a new source of revenue—advertising. Railroads, the telegraph, and advertising enabled entrepreneurs to market their goods nationwide. The commercial use of the telegraph became a vital ingredient in the industrial mix that turned the United States into a world economic powerhouse.

The Increasing Speed of Communication

Before the Morse Code revolutionized communication, the fastest way for news to travel was via a courier riding a fast horse. Word of the Battles at Lexington and Concord, April 19, 1775, the first bloody confrontation of the American Revolution, did not reach Williamsburg, the capital of Virginia, until April 28, nine days after the fight. It did not reach London for another month, May 28. In contrast, a message carrying the news of Samuel Morse’s death less than a century later reached India in a few hours.

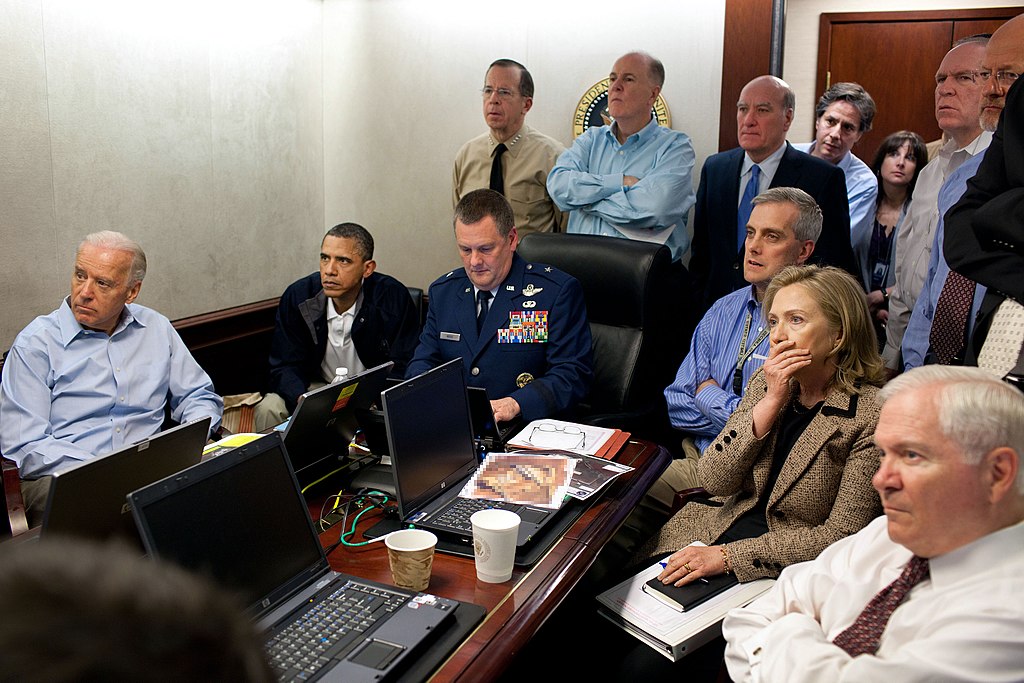

Information from the battlefield arrives in our homes much faster today. President Barrack Obama watched the mission that carried out the killing of Osama bin Laden from the situation room in the White House. Although I am far from an expert on electronic communication today, it strikes me that, in some ways, we still follow Samuel F.B. Morse’s approach. I hit specific keys on my keyboard, and a computer code turns them into understandable text. Another system of computer codes instantly transmits my draft to my colleagues in California and Colorado. They polish my draft and post it, using other computer codes on the Teaching American History website. Perhaps students would be more likely to see history as a part of their lives today—not simply events in the past—if we help them see that the technology we use today uses countless advances from great minds in the past. When they text their friends, are they not operating a code—not unlike dots and dashes—that makes their message accessible to the person receiving the text? What kind of picture would that paint for students to consider?

Ray Tyler is a MAHG graduate and a former Teacher Programs Manager at TAH.