Teaching American History has recently published World War I and the 1920s: Core Documents, a collection curated by Professor Jennifer D. Keene, Professor of History and Dean of the Wilkinson College of Arts, Humanities and Social Sciences at Chapman University. Keene, a specialist in American military experience during World War I, has published three studies of this subject, along with numerous essays, journal articles, and encyclopedia entries. Keene also edited our collection of core documents on World War II (2018, 2nd ed. 2022) and teaches courses on the World Wars and Modern America for the Master of Arts in American History and Government program at Ashland University. We asked Keene to highlight some of the most interesting documents in the collection.

- Some of the documents you curated for this volume are well-known but perhaps not well understood. Would you discuss a document that merits more careful study?

I’d recommend the excerpt of Wilson’s speech to Congress on “The Fourteen Points” (January 8, 1918, Document 14). Textbooks and document collections often give us very brief excerpts of the speech, including only Wilson’s fourteen proposals—or only some of them. In this collection, I try to contextualize the document to help teachers and students see all of its implications.

The parts of the speech that frame Wilson’s proposals—his introductory and concluding remarks—remind us that he’s giving the speech at a very important moment in the war. Lenin and the Bolsheviks have just taken control of the Russian Revolution.

When Wilson gave his war address on April 2, 1917, the first, democratic revolution in Russia had just occurred. Wilson was very hopeful that democracy would take root there. Now, as he thinks about negotiating an end to the war, he’s confronted with the possibility that this will not be a war to safeguard democracy, but rather to promote communism. At the same time, the new Bolshevik government is engaged in peace talks with Germany. Once Russia exits the conflict, Germany will be fighting a one-front war and may be able to defeat the Allied powers before American troops can join the fight.

These new circumstances don’t dampen Wilson’s idealism. He still hopes to devise a plan that will eliminate future causes of war. The Fourteen Points outline what Wilson believes are the war’s causes—territorial borders that disregard traditional national groups; colonial ambitions; violations of the freedom of the seas; the stockpiling of armaments. Yet the speech also shows Wilson offering an olive branch to Germany. He envisions a peace in which Germany retains a place of “equality” with the other nations involved in the current conflict.

Most scholars and textbooks contrast the Fourteen Points speech to the Versailles Treaty, which did not treat Germany leniently. Yet when you compare the Fourteen Points speech to the speech on the Charter of Atlantic Freedoms that President Franklin Delano Roosevelt delivers in August 1941, you see that Wilson’s ideas live on.

- Wilson’s idealism seems unrealistic given the imperial ambitions of most of the combatants. Yet later, when he defends the Versailles peace treaty (Document 24), Wilson claims to have brought to the negotiations at Versailles nothing more than the views of his American constituents. Is he reflecting American opinion, or projecting his own ambitions as a peacemaker?

Yes—he does project a messianic attitude. And yet the ideals he expresses are those that persuaded Americans, for the first time in their history, to enter a war in Europe.

- Would you comment on some less well-known documents you included, ones that widen our understanding of World War I and the 1920s?

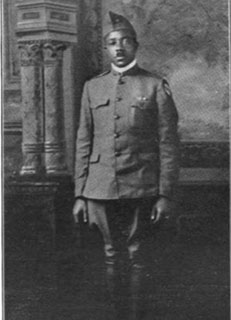

The documents I love are those with rich connections to other documents and historical issues. Such a document is Charles Isum’s letter to W. E. B. Du Bois (Document 21). Isum is a Black veteran, a sergeant in the medical detachment of the one fully functioning African American combatant division in the US Army. Once home, he reads Dubois’ editorial, “Returning Soldiers” (Document 20) in The Crisis, which Du Bois edits for the NAACP, and decides to write a letter in response. Du Bois’ editorial called for resistance to racial discrimination and harassment, and one might wonder whether the editorial made an impact in the Black community. In my research on the African American soldiers’ experience during and after the war, I found this response to Du Bois. It demonstrates the editorial’s importance. Isum’s letter begins by saying, in effect, “I read your editorial—and let me tell you what happened to me in France.”

In France, Isum is quartered with a French family and warmly welcomed by them. They see him as an American ally who’s helping them in their struggle against Germany. But his white American Army officers object when he accepts an invitation from his French hosts to attend the wedding of their daughter. Isum’s story illustrates both the sense of widening social possibilities that black soldiers experienced overseas and the attempts of white superiors to suppress this awakening. France, which held colonies in Africa, was not a colorblind society; but the French saw the African American soldiers not as colonial subjects but as American allies and liberators. In fact, the liberating experience African Americans enjoyed in France helped to galvanize the modern Civil Rights Movement. Isum’s letter recounts the indignities he suffered at the hands of white Army officers, but it also shows him successfully fighting back against their attempts to punish him for accepting social invitations from the French by pointing out the rights associated with his rank. What underscores the impact of this World War I experience on later Civil Rights efforts is the lineage between Charles Isum and his daughter Rachel, who watched and learned from her father’s activism. She eventually marries Jackie Robinson, the first African American to play in Major League Baseball. Jackie and Rachel Robinson walked in the footsteps of Charles Isum. We often forget that it took the efforts of earlier generations to lay the groundwork for the Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s and 1960s. In America, we like unequivocal success stories. We tell the Jackie Robinson and Martin Luther King stories; but we don’t celebrate the activism of the generations before them, whose success was incomplete, but nonetheless important.

- How about a document on the 1920s?

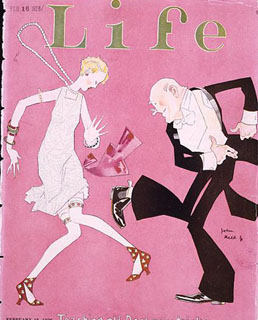

I love the essay “Me and My Flapper Daughters,” written by the journalist William Oscar Saunders (Document 35). He assumes the persona of a father who’s perplexed by the behavior of his two daughters, who adopt the behavior patterns and fashion styles of the “flappers” of the 1920s. The first-person narrator of this story (it is fictionalized, at least in part) attempts to reconcile the youthful rebellion of his daughters with his hopes that they’re going to be safe and happy in later life. During their adolescence, these young women are smoking, drinking, and going out on unsupervised dates with young men who drive them in cars to lovers’ lanes. The document gives you some insight into the youth culture of the 1920s, the generation that would grow up to experience World War II as adults. It describes the generational conflict that occurred in the 1920s, but resolves the tension by concluding that this youth rebellion is really just good clean fun. The narrator confides his certainty that in the end, his daughters will settle down and get married.

When I use this document in seminars, teachers always want to talk about it. It’s written in a light, humorous tone, but it also offers some insight into what actually happens after women achieve the vote. Like the letter exchange between a soldier deployed to France and his working wife (Document 17), and the letters from women printed in the Home Companion excerpt (Document 31), Saunders’s essay shows that women still find their opportunities limited by gender expectations. There is a narrative that war liberates women. That story is misleading, yet really hard to shake. We have to be careful not to attribute too much transformative power to war.

Recent Comments