(RNS) — In the hit new video game Starfield, players can explore strange new worlds, battle space pirates and rescue civilians from deadly aliens. Along the way, they can find enlightenment in simple acts of human kindness or in solitude among the stars.

But as in the real world, the meaning of life proves elusive.

“If you find it, be sure to come back and let me know,” one of the game’s clerics tells the main character during a visit to a temple. “It would make the next sermon more memorable if nothing else.”

Lead designer Emil Pagliarulo of Bethesda Game Studios told Polygon.com that he and his colleagues wanted to challenge players not to just explore the universe but also to think about what the universe means.

Along with all the other tasks common to role-playing games — acquiring resources, building up experience, fighting enemies and fulfilling quests — players have a series of transcendent encounters with alien artifacts, filled with light and sounds, as well as out-of-body experiences.

When the encounters are over, they have a chance to talk about what those encounters mean: Were they signs God exists — or just a weird trip?

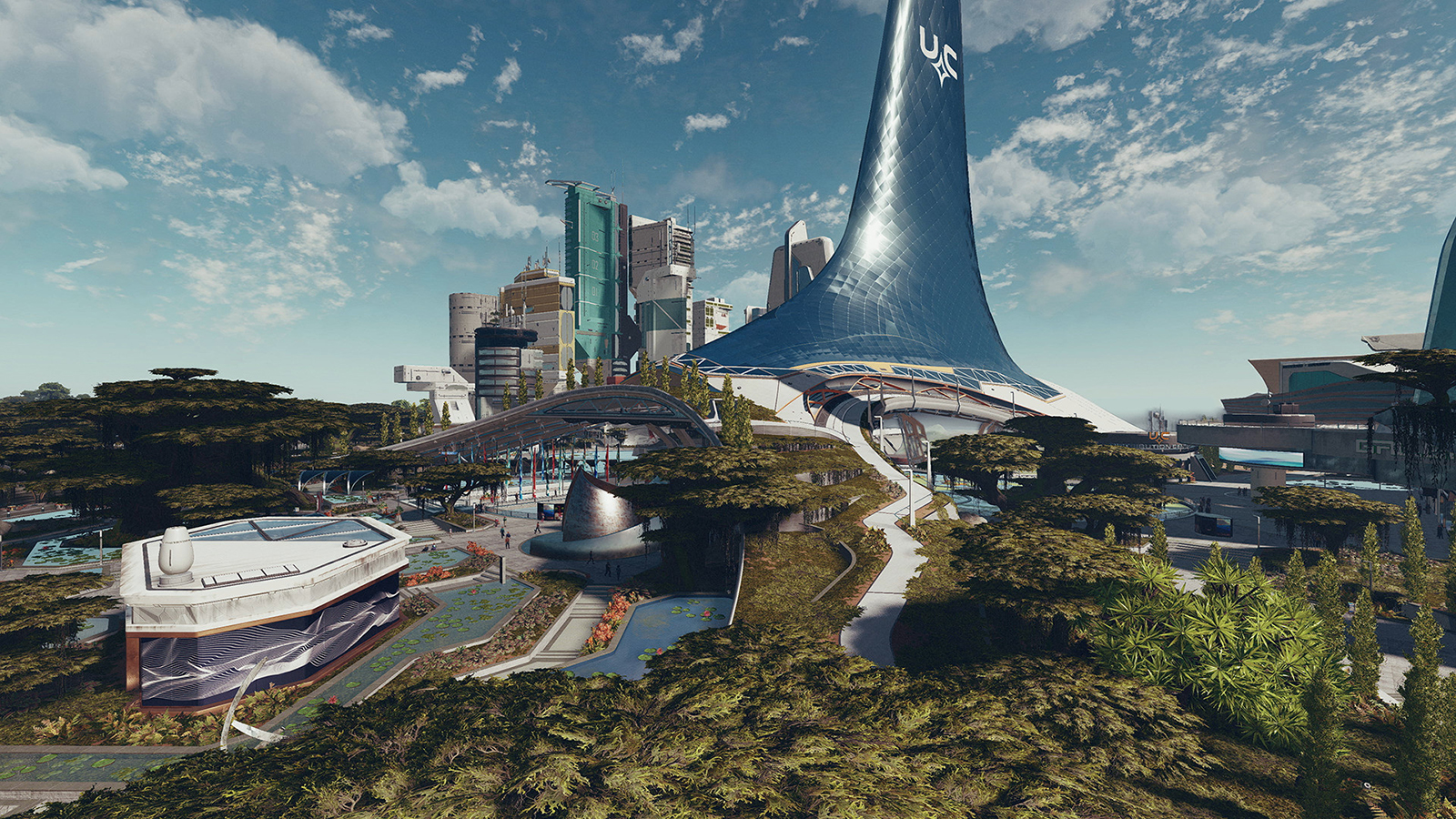

Image courtesy of Bethesda Game Studios

Players also can choose to join one of the game’s three religions: the Sanctum Universum — a faith designed by a Bethesda staff writer turned Jesuit — that sees all of reality as holy; the Enlightened, which believes in human kindness but not in God; and House Va’ruun, an apocalyptic death cult.

The first two faiths get along fine with almost everyone. The death cultists, as one might suspect, are viewed with suspicion, and spend most of their time trying to blow up other spaceships in God’s name. By contrast, players who join the Enlightened are asked to help a sick homeless man find his way home from the hospital and to pick up soup for him on the way. Those who join the Sanctum Universum ponder the big questions of life.

“Is God real?” one of the group’s fictional texts asks. “The more proper question would be, ‘Is reality divine?’ Existence itself is a mystery which yearns to be uncovered.”

Richard Clark, host of the “Video Game Feelings” podcast, said the scope of the game — there are more than a thousand worlds to explore, many filled with people who need help or who have their own intricate storylines — makes players think about the vastness of space and how humans fit into it.

Clark, former editor-in-chief of the Christ and Pop Culture website, said he’s been playing games for as long as he can remember, beginning with Atari games with his dad as a kid. In Starfield, he was struck by a mission where his character ran into an old Earth spaceship whose passengers had been traveling for 200 years to a new homeworld. His character had to break the news to them that the planet was already occupied, which shattered all their assumptions about life.

“That sort of brain-breaking moment is what the gamer is going through,” he said. “They are thinking, ‘There is a lot happening here and I don’t know how to process it.’”

Image courtesy Bethesda Game Studios

Starfield also allows gamers to choose whether to play as a hero, a callous mercenary or even a pirate. They can try to de-escalate conflict by persuading their opponents to back down or paying them to go away. Or they can simply start shooting.

Clark said he tends to play video games the way he would behave in real life — being a peacemaker rather than choosing violence and being the good guy when he can. When he failed to do so in Starfield, the nonplayer characters, better known as “NPCs,” would look down on him. When he succeeded, they’d praise him.

“I could write a whole essay about gaining self-doubt and self-confidence from other people’s opinions of you,” he said. “And how it wears off.”

Tracie Simer. Courtesy photo

Tracie Simer, a former religion reporter and game store owner turned part-time dungeon master for tabletop games, said the game’s morality seems to change the longer you play. As the NPCs get to know your character, she said, they become less judgmental and more willing to live and let live — a little bit like real life.

She appreciated that the game’s developers portrayed religion in the game in a positive light. Other games, she said, have used religion as a source of conflict or painted it in a negative light. Simer said she also appreciated that choosing one faith didn’t make other characters look down on you.

That lack of hostility toward religion was refreshing, she said.

Mark Wolf, chair of the communication department at Concordia University Wisconsin and author of “Building Imaginary Worlds,” said religion has long played a role in popular video games. He pointed to Myst and Riven, both released in the 1990s, whose creators’ Christian faith played a role in shaping the popular puzzle adventures, which sold millions of copies. The games themselves, he said, could be a contemplative experience.

Other games, such as EVE Online, a multiplayer space adventure known for its legendary space battles involving players around the world, have also included religion in their world-building. Unlike Starfield, Wolf said, some of those games have allowed players to create their own religions.

Image courtesy of Bethesda Game Studios

Ben Chicka, a lecturer in philosophy and religion at Curry College in Milton, Massachusetts, said religions in Starfield are depicted more carefully than in some other games he has seen — especially if they take place in a post-apocalyptic world.

In Starfield, humanity abandoned Earth when it became unlivable and most of Earth’s solar system became deserted. Fleeing to the stars led to the creation of at least one religion in response to the vastness of space.

Isaac Bradshaw, a school counselor and Anglican Church in North America priest from Maryville, Tennessee, approved of Starfield’s approach to religion. For some characters, religion is central, while for others, it’s simply one part of their identity.

Isaac Bradshaw. Courtesy photo

“I think this approach is almost more real in the way that people operate their spiritual life in the 21st century,” he said. “It’s an option you get when you build your character and it operates in the background. You get to choose the extent to which that background influences your choices.”

Bradshaw said video game stories have evolved from more simple games like Super Mario Brothers — where the goal was to save a princess from a dragon — to deeper stories about life. He sees games like Starfield as “icons” — imperfect images that reflect something divine.

He pointed to an earlier space game called BioShock Infinite, which begins and ends with baptisms — the first one forced, the second an act of sacrifice when the main character drowns and by doing so saves the universe.

“I am all in on the idea that somebody dying resets the world,” he said.

Religion in Starfield does include some surprises. During an important side mission, a leader of House Va’ruun provides a vital piece of information that will help save colonies from deadly alien monsters. While that leader still worships the apocalyptic cult’s Great Serpent God, he wants to save people, not kill them. By doing so, he hopes to undo some of the evil done in his god’s name.

While she’s enjoyed the theological and religious elements, Simer said she drew some lines in the sand. Playing a “mean person” was a nonstarter. As was joining an apocalyptic cult.

“If I have the choice to join what is basically the Universalist church of the United Federation of Planets versus a death cult — I’m going to choose the Universalists,” she said.

Image courtesy of Bethesda Game Studios